Be like Clyde

Image courtesy of NASA

In 1930, during the biting cold nights of February, just a short drive south of the Grand Canyon in Arizona, Clyde Tombaugh gathered himself underneath a large metal dome. No heaters were allowed inside the dome, warming the air would cause perturbations that would warp and confuse the paths of light trickling in through a gap in the metal above him. The light, pricking holes in the dark desert-like sky above Clyde, were (mostly) stars. That night and every night for nearly a year, he would gather their light in a large telescope that belonged to the Lowell Observatory where he was currently working tirelessly. But Clyde was not interested in stars: not on this night anyway. Clyde was looking for something much nearer, and yet still so very, very far away. He was looking for what the telescope’s builder called, Planet X: a giant planet that was supposed to explain Neptune’s strange orbit, accused of tugging and corrupting Neptune’s path with its gravity. Clyde Tombaugh did not find Planet X, but he did find something else, an object fascinating and distant and desolate and now infamous. On the 18th of that winter month in Arizona, Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto.

Tombaugh was born in 1906, he grew up on his parent’s farm in Illinois where, before he was even tall enough to start peeping over the swaying crops of his father’s fields, he started to develop a profound fascination with the night sky. His father, bucking the stereotype of working-class farm father figures, encouraged his dreamy interest in the heavens and even picked up a second job to afford Clyde the materials to build his own telescope. Though, constructing his own device would not be enough for someone as ambitious as Clyde. He also dug an enormous pit in one of the fields to house his new invention – protecting it from the turbulent atmosphere and allowing him to observe the planets Jupiter and Mars in wonderfully precise detail. Details that he translated into the drawings you see below. Tombaugh posted the sketches to the Lowell Observatory, in what amounts to the 1920s version of an unsolicited LinkedIn job hunt message. Though he didn’t actually ask for a job, only their thoughts on his efforts, they returned to him an offer for the position of Junior Astronomer*.

Tombaugh’s drawings that he sent to the Lowell Observatory. Source: Business Insider

The Lowell Observatory was founded some thirty-four years before Tombaugh arrived, but the discovery he made would seal its place in history. Discoveries like this rarely come easily, however. The campaign to expose Percival Lowell’s Planet X was a laborious one. Tombaugh baked images of the night sky on to photographic plates. Using a ‘blink comparator’ he would flick between images of the same portion of sky separated by a few days in time, searching for anything that moved between images. Background stars in the images are so far away that they don’t move, or at least their movement is imperceptible, any object that scuttles across the plates, in front of the stars is invariably a solar system object. Tombaugh was essentially playing ‘What’s the difference’ with the Universe: and in 1930, Clyde won that game.

Out in the deep dark, shadowy outskirts of the solar system, his object drifts seemingly alone. Pluto lies 6 billion km away from the Sun, some forty times further out than the Earth. These cosmic landscapes are cold and icy, and Pluto is the epitome of this description. Named after the Roman God of the Underworld, Pluto is made of rock covered in frozen nitrogen - an element that exists as a gas in our atmosphere - and mountain ranges of water frozen harder than granite rock. Pluto has five moons swirling around it, all equally frosty and inert. They have good names though, keeping up the dramatic mythical theme with Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. The largest, Charon, is more than half the size of the planet itself, and that leads us to the one hitch in this otherwise perfectly crafted story of heavenly discovery: Pluto is damn small. In fact, it was officially certified by the International Astronomical Union as being “quite weeny”, which they updated to “not a planet” in 2006.

Pluto’s demotion to a dwarf planet was a disappointment for many, but the disappointment for Tombaugh and his predecessors came much earlier; at the realisation that Pluto was way too small to be the speculated Planet X that he was searching for in the thousands of images he scoured. Over seventy years, Pluto’s estimated mass went from fifteen times higher than Earth before it was found to just one-hundredth of Earth’s mighty bulk these days. Tombaugh achieved great fame with his discovery and he continued the hunt for glory by searching for other planets like Pluto out in the far reaches of the solar system. Tombaugh searched millions of photographic plates, finding many asteroids and the like, but never another planet. He concluded that Pluto was the only one to be found. Tombaugh was wrong.

It was astronomers’ discovery of a number of bodies with similar size to Pluto (if not bigger), that called the definition ‘Planet’ into question. If Pluto was to retain its title, then about one hundred other solar system objects would also be planets, and all of a sudden any song or acronym you use to remember the order of them would look like it was written in Welsh. And so it was, that Pluto picked up the prefix ‘dwarf’ and became one of many ‘Guardians of the Underworld’ in a region of space we now refer to as the Kuiper Belt. Tombaugh’s object may have been small and common for that part of the solar system, but it was the first piece of a far bigger, far more chaotic puzzle. Irrespective of Pluto’s size and uniqueness, the intrigue this creeper at the edge of the solar system could conjure was not muted by these other findings.

In the very same year that Pluto was relabelled as a dwarf planet, NASA launched a pioneering mission to flyby its surface with a probe named New Horizons. New Horizons broke records of speed and badassery, and it did some rather impressive science as well. Science that surprised planetologists the planet over. High-resolution cameras aboard New Horizons revealed details that even Clyde Tombaugh with his sharp eye and steady hand could not match. Among those details were strange patterns on the surface of Pluto’s frozen nitrogen flats, that looked like clusters of cells as opposed to the expected smooth coating of ice. This was evidence of convection - rising heat from the interior - pushing up through an ocean of liquid water. And you know what they say about liquid water, that old catchy phrase, “The presence of liquid water may be an indication of the potential for life-sustaining environments!”.

Ending this story with the revelation that Pluto, at its unbelievable distance from the Sun, may be a possible harbourer of life seems appropriate, but there is one last beautiful twist. As New Horizons coasted past Pluto, on a trajectory that would take it out of the relative unknown of the solar system into the very unknown of interstellar space, it carried with it a most precious passenger. About 30 grams of organic molecules broken-up by flames and oxidised into ashes. Safely stowed away on the probe, Clyde Tombaugh finally met his precious planet. The remnants of his body and the full might of his spirit were united with Pluto. Once just a boy in a field with a home-built telescope and an eye full of wonder, now destined to sail across space for evermore.

Remember: Be like Clyde.

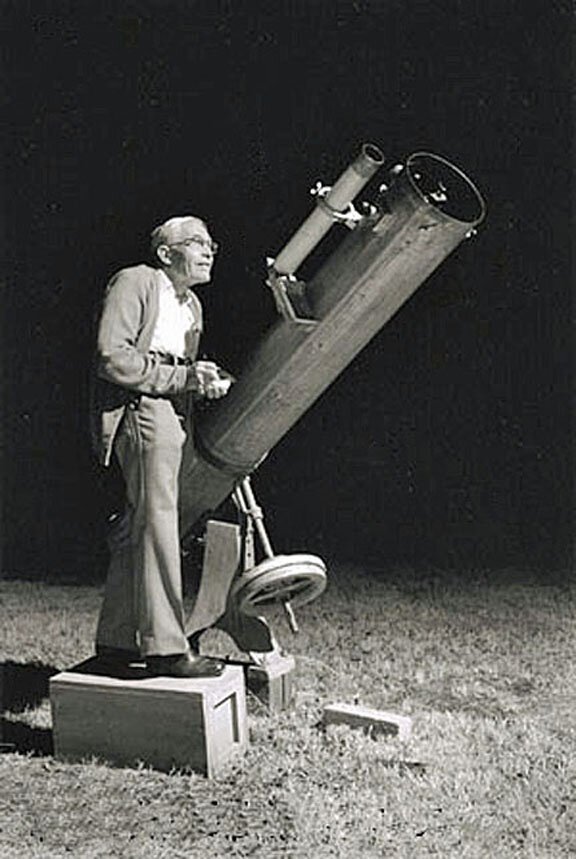

Clyde doing what he did best. Courtesy of the Lowell Observatory

*Note to self: send this blog to NASA asking for their “thoughts"